On being gay in Lebanon: Beirut cannot be Mykonos or London, and that is okay

Yasmine Ben Abdessalem

“To achieve gay liberation, Beirut cannot be Washington or London - same fight, different grounds; in fact, perhaps a different fight altogether because it has London and Washington in its satellite” (Dabbous, 2019)

Beirut as an Arab city is often portrayed as being open to difference and experimentation. This portrayal is reinforced by the existence of rather openly gay and lesbian events, clubs.

Often, in the public sphere, Arab countries are depicted as backward-looking when it comes to their laws on sexuality, and especially on non-heteronormative relationships. There is a binary distinction between the East and the West, that separates them into two antithetic entities, without actually understanding the impact of the West’s influence on countries like Lebanon.

Source: https://www.archdaily.com/946829/beirut-between-a-threatened-architectural-heritage-and-a-traumatized-collective-memory

Centuries ago, around 1350, Rumi and Hafiz, two Arab male poets wrote about men in affectionate, even amorous, terms. This was not a new practice and was not seen as unusual at the time, as it was widespread in the Middle East. It was seen as part of a refined sensibility. At that time, sodomy was the only act that was deemed a sin, and all other acts such as kissing were accepted, both by society and by the legal system. In 2013, the Pew research center conducted a survey, and found out that 80% of the people in Lebanon think that “homosexuality should be rejected”. What explains this change of attitude towards homosexual relationships? In fact; How did colonization impact the perspective on homosexuals in Lebanon?

COLONIAL LAWS AND HOMOSEXUALS IN LEBANON

Lebanon was colonized by France after the First World war, until 1943. When colonizing the country, French laws, regulations, and norms began to be applied in Lebanon. The first way in which colonization impacted the treatment of homosexuals was through regulation. French laws were highly influential in the treatment of homosexuals, by using penal codes that criminalized “all homosexual behavior”, although implicitly. These peripheral sexualities were targeted through the Napoleon code used by the French authorities. In Lebanon, the “penal code 534” exemplifies the idea that homosexuals are at risk since this code enabled the state to punish unnatural sex.

What is striking is that these laws don’t ban homosexual acts explicitly, rather it bans “ unnatural sexual acts”, therefore leaving it to judges to decide what can be considered as natural or not. The consequences of this penal code are various, with a prison sentence between one month and one year, and a fine that can go up to one million Lebanese pounds.

Since these qualifications of “unnatural sex” are vague, the police’s power to arrest LGBTQ people is wider. In 2014, the police in Lebanon “orchestrated a raid on a hammam”, where men were arrested, subjected to compulsory HIV tests, and forced to confess. This shows that the legacy of the French colonial rule through laws and regulations still has an impact on non-heteronormative sexualities in Lebanon.

Nowadays, although homosexuality is implicitly illegal in Lebanon since people can be imprisoned for it, Western articles still claim that “Beirut is safe for gay western tourists”.

Magazines focused on gay tourism assert that the Lebanese are familiar with the concept of homosexuality as a result of the French penal code. Luongo, an editor that writes about gay travels in the Muslim worlds asserts that the Arab areas that were controlled by the French during the colonization, are the “ones with laws against homosexuality” because the French were eager to talk about sex. He furthers argues that French history contributed to the familiarity and the normalization of homosexuality, which is actually, not the case.

Colonies; Sexually Permissive Societies? The issue of Discourse

As Foucault argues, since the 18th century, the discourse about sex has changed and intensified. This discourse created this urge to classify and specify individuals according to their perversions, and thus started the “persecution of peripheral sexualities”, namely sexualities that did not follow a heteronormative pattern.

By doing this, colonies were presented as “sexually permissive societies”, that needed to be controlled in terms of their sexual behavior. Additionally, the field of Arab psychology has been influenced by the discourse on sexuality coined by European powers around the time of colonization. Psychologists started to use the term “sexual deviance” around 1950, which became widely used in the media and in polite company to refer to the Western concept of homosexuality in Lebanon. This created awareness about homosexuality and heterosexuality was, as a reaction successfully implemented among the upper classes and the increasingly Westernized middle classes.

Even after the independence of Lebanon, and as non-heteronormative types of sexuality became increasingly accepted in the West through for example the legalization of gay marriage, the perception of homosexuality stayed the same in Lebanon. It was now seen as an integral part of the Western cultural onslaught against ‘authentic’ Middle Eastern cultures. Foucault argues that “identity is culturally constructed through a series of exclusions”. When following this perspective, we can say that in Lebanon, negating non-heteronormative sexualities such as LGBTQ+ ones, permitted them to reclaim their own culture.

There are elements in the discourse of colonial representations that justified colonial conquest all over the globe. Mc Clintock coined the idea of pornotropics ; settlers and colonizers discovered lands beyond the West, where everything that is sexually prohibited in Europe is allowed. Mc Clintock explains that there is a tradition of traveling as an erotics of ravishment in countries where norms and boundaries that restrain sexuality in Europe, are not present. Continents such as Africa were “ libidinously eroticized”. By traveling there, Europe projected its forbidden sexual desires and fears. This can be seen nowadays through the promotion of “gay tourism” in Beirut, the capital of Lebanon. This depiction of gay tourism can find its roots in orientalist depictions of both place and people”.

“Beirut has often been designated by the media as the Paris of the Middle East”, the Amsterdam of the Middle East for its liberal character, and relative open atmosphere, the prominence of its nightlife compared to other Arab cities, especially for the gay community”.

Beirut is explicitly compared to cities in European terms to make explicit the difference between this city and other Arab cities, to represent the different Middle East for homosexuals.

In another article, the author claims that Lebanon is different because “the Lebanese are descendants of the Phoenicians, a society that became one of the greatest civilizations precisely because they were open to new things”. This shows that the “openness” of Lebanese people is assimilated to Ancient times, and historical events that do not fit into modern history. These depictions on magazines of gay tourism enhance a colonial narrative that is thematized as in those voyages to the Near East, imagined by Western men.

Beyond Colonization: a Pervasive Influence

One could argue that Lebanese people are both constructed by the colonizer’s discourse and practices, but that they are also trying to detach themselves from it. As mentioned previously, the West became increasingly eager to accept and tolerate non-heteronormative sexualities after the Stonewall period, and countries in the Middle East, such as Lebanon took the opposite turn to reaffirm their own opinions. In the meantime, LGBTQ+ people of Lebanon resorted to Western NGOs referred to as the Gay International, to gather help, fair treatment, since they could not find support in their government.

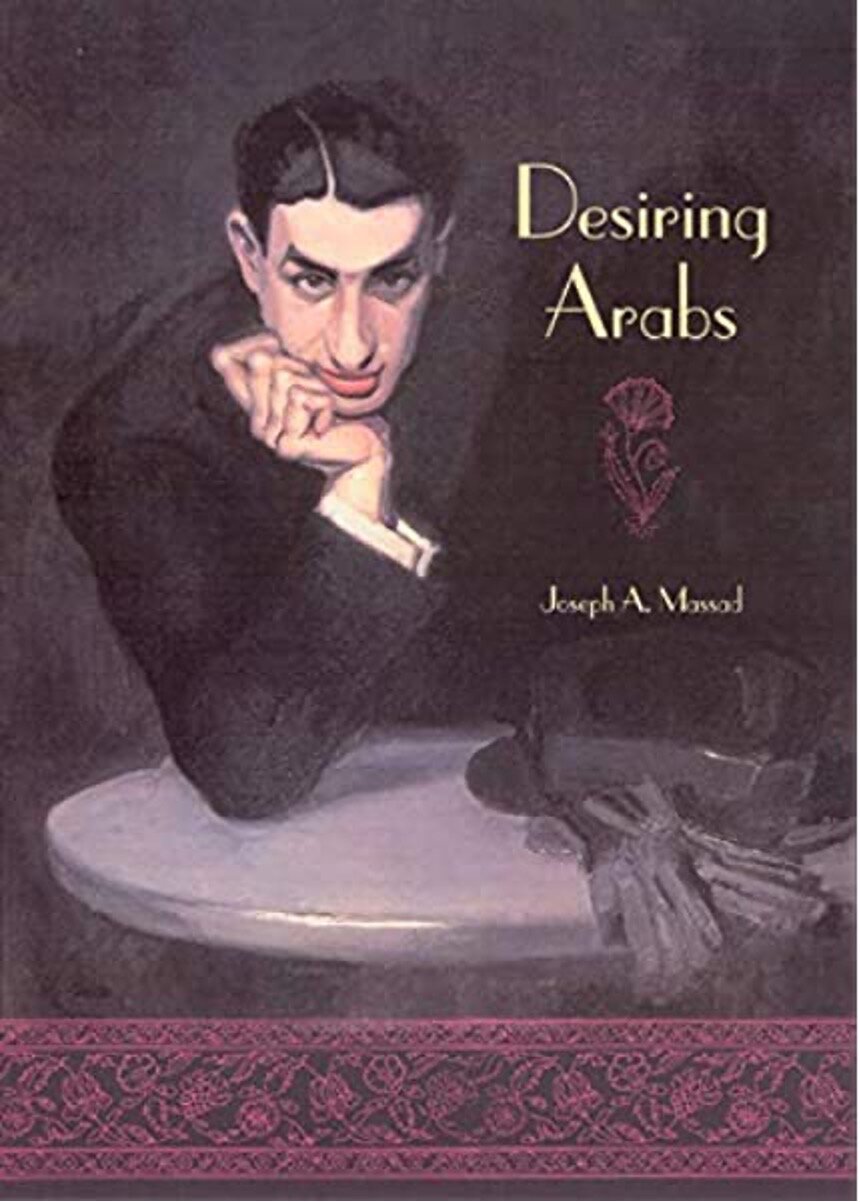

Joseph Massad, a prominent academic coined the idea of the “Gay International” as the idea of gay-rights-based movements that adopted a missionary role in the Arab World. He argues that the West’s willingness to protect the rights of homosexuals is linked to its hegemonic project, which is underpinned by exporting concepts such as homosexuality. Massad doesn’t believe that the category “homosexual” exists similarly all over the globe, but rather thinks that the Gay international is responsible for “creating the homosexuals”, and by doing that, it harms people that engage in homosexual activities in the Arab World. The issue with the discourse of the Gay International is that it assumes that homosexuals, gays, and lesbians are universal categories that exist everywhere in the world which gives grounds to their missionary actions.

[1] Massad’s argument can be problematic because denying the existence of the category “homosexual” engenders negating their rights and their existence. But his argument is interesting to highlight in this case.In fact, the agenda of the Gay International, that the West internationalized in the 1980s made homosexuals’ conditions worse, as they became the two targets of human rights violations in Arab countries.

The early 1980s witnessed the rise of Islamic fundamentalism, which coincided with the internationalization of Western gay movements. This leads to a discourse about “Western sexual deviance” that was later portrayed in an even more negative way in the Arab press with the apparition of AIDS.

Therefore, it is the “sociopolitical identification” of these practices with the Western identity of homosexuals that is being repressed, rather than same-sex practices in Lebanon. Most Arab countries did not have explicit laws condemning sexual contact between men, but as a critique of the GayInternational’s incitement to discourse, they started professing anti-homosexual stances on nationalist, anti-imperialist grounds.

The importance of Reappropriating the discourse on sexuality in Lebanon

In Nadine Labaki’s movie Caramel, produced in 2007, the topic of homosexuality is touched upon, however, in its own terms, in opposition to the mainstream portrayal of explicit homosexual characters in the West. This movie retraces the lives of five women who work in a hair salon, and their everyday navigation in social places, that are limited, shaped, enhanced by practices of concealment and revelation. This movie explores ambiguously a romantic attraction between two women, through the prism of secrecy.

The movie director Labaki enhances this aspect by explaining that in Lebanon, neither men nor women are at ease of being able to navigate their sexualities between the Western example of the very liberated man on one hand and the rules and traditions on the other.

The director also points out an interesting notion relative to sexuality in Lebanon. Labaki says that girls in Lebanon are raised with the word ‘ayb’ (shame). This shame makes women in Lebanon afraid to commit acts that must not be done, and that personal sacrifice is valued in the face of pleasing parents, children, men, and families. This appears to be contradictory to the “Gay International” ideals of coming out, and of being proud and shameless of one’s queerness.

Labaki’s portrayal of these women’s sexualities relates to Massad’sargument, by having a lesbian protagonist that is not necessarily eager or willing to come out, and would rather live her attraction under the prism of discretion. To have a fair and authentic representation of homosexuality in Lebanon, As Labaki puts it, “ You have to cheat in a way where people get the message without bluntly seeing it”. The notion of shame is an important aspect of homosexual relationships in Lebanon.

Events such as pride, although had positive effects for communities by gaining social recognition, also eroded its goals of achieving queer shamelessness. This appears to be especially true for queer people in Lebanon, that are at the same time shamed locally for infringing socio-moral codes, but also globally for being too gay or not gay enough. As a reaction, Beirut pride claimed that it is not a “westernized, imported” event but rather a local-based platform, that reflects on the Lebanese complex social fabrics. Still, it was canceled in 2018 because of its westernized feel, rather than its queer content. It displayed Hollywood movie references, rainbow flags, Grindr catchphrases, that were seen in direct opposition to Arab’s homosexual equivalents.

On another note, Beirut’s first gay NGO “Helem” appears to work in the opposite way that the Gay International. Helem does not focus on the internationality of the movement but uses communication strategies that emphasize “Arab feel posts”, avoiding western-like imagery. This allows them to claim their own demands but also guarantees them to avoid censorship.

In Bareed Mista3jil, a book published by Meem, a recollection of testimonies from young queers in Lebanon displays their perspective on their queer experience, deviating from the heteronormative standards, whether they are Muslims, Christians or atheist, rich or poor. The author explains that Western constructions of sexualities have been influential but that these identities still are anchored, and evolve in a specific local context, in Lebanon. A majority of these people talking about their experience do not want to compromise their family life, traditions, and modern queer life. These storytellers often emphasize the notion of shame, towards their family and society.

Most of the young people in Lebanon, also cannot find a compromise between Arab culture and being queer as mentioned on page 233:

“At the time, it felt like my final arrival to queerness was also my adieu to Arab culture—no thanks to my mother, who insisted that homosexuality did not belong to Arabs”

Young queers in Lebanon feel triggered by the expression of their sexuality as it is often seen as something that belongs to the West.

Queer Lebanese also reflected on “family pressure” in their testimony, and the fear of being ignored and ostracized (idem: 247). A woman explains in her story that being queer for her is not only about her personal sexual orientation, but also about “being aware of my family and how they are feeling” because she feels like she owes them a lot. She furthers explains “ .. They have done so much for me that I just can’t say <<yalla, bye>> to them”

Source: https://www.thedailybeast.com/the-myth-of-the-queer-arab-life

What is there left to do? To conclude…

Colonization impacted the perspective on homosexual relationships in a myriad of ways in Lebanon. Through laws, discourse, and representation in the media, homosexuals are either misrepresented by the West, either victimized, or either denied total agency and seen as puppets of the Gay international in the eyes of Arab countries and governments. Slowly, the discourse is changing, as in July 2013, the “Lebanese Psychiatric Society” stated that “homosexuality is not an illness and does not need treatment” which contributes to less pressure towards the homosexuals in Lebanon. From the point of view of the law, in the past 10 years, four judges refused to criminalize homosexuality on the ground that the constitution and the penal code that punishes “unnatural sex acts”, as they pointed out that it should not apply to consensual same-sex relations.

SOURCES :

A.L, 2018. How Homosexuality Became A Crime In The Middle East. [online] The Economist.

Dabbous, R., 2019. The Obstacle To Gay Rights In Lebanon: Homophobia Or Westphobia?.[online] openDemocracy.

Dalacoura, K., 2014. Homosexuality as cultural battleground in the Middle East: culture and postcolonial international theory. Third World Quarterly, 35(7), pp.1290-1306.

Fisher, M., 2012. The Real Roots Of Sexism In The Middle East (It's Not Islam, Race, Or 'Hate'). [online] The Atlantic.

Georgis, D., 2013. THINKING PAST PRIDE: QUEER ARAB SHAME INBAREED MISTA3JIL. International Journal of Middle East Studies, 45(2), pp.233-251.

Hudgins, S., 2016. Why Is Lebanon Still Using Colonial-Era Laws To Persecute LGBTQ Citizens?. [online] Slate Magazine.

İlkkaracan, P., 2008. Deconstructing Sexuality In The Middle East. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Jackson, S., 2006. Interchanges: Gender, sexuality and heterosexuality: The complexity (and limits) of heteronormativity. Feminist Theory, 7(1), pp.105-121.

Lugones, M. (María) (2010). “Toward a Decolonial Feminism,” Hypathia. A Journal of Feminist Philosophy, 25(4): 742-759.

Mandour, S., 2019. LGBT In Lebanon: 15 Years Of Activism, Oppression. [online] Asia Times.

Massad, J., 2002. Re-Orienting Desire: The Gay International and the Arab World. Public Culture, 14(2), pp.361-386.

Meghani, S. and Saeed, H., 2019. Postcolonial/sexuality, or, sexuality in “Other” contexts: Introduction. Journal of Postcolonial Writing, 55(3), pp.293-307.

Mourad, S., 2016. The Boundaries Of The Public: Mediating Sex In Postwar Lebanon. PhD in Communication. University of Pennsylvania.

Moussawi, G., 2013. Queering Beirut, the ‘Paris of the Middle East’: fractal Orientalism and essentialized masculinities in contemporary gay travelogues. Gender, Place & Culture, 20(7), pp.858-875.

The Economist, 2013. They’Re Not Ill. [online] The Economist. Available at: <https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2013/07/20/theyre-not-ill>